In this month’s article I will be covering every racing driver’s dream….racing in the rain!

You may have heard of the rain as “the great equalizer.” This is the well known theory in racing that the rain skews the performance responsibility more towards the driver and less towards the car. This is why you see a lot of drivers (especially the fast ones) prefer these type of tricky conditions.

Ever see some random midpack driver that you’ve never heard of come charging through the pack and end up winning the race?

This happens often in the wet and it’s no coincidence.

In these type of conditions what the driver does matters more, and the performance of the car matters less.

And it’s a satisfying feeling when you kick butt in the rain because it’s worth some serious bragging rights (especially amongst top racers) because you won in the most adverse conditions.

Let’s get into it.

The performance variables have changed.

In most of my articles I bring up the 3 driver performance variables. Grip (G), Radius (R), and Distance travelled (D).

In all circumstances, these are the only three variables that the performance driver has as influence over when it comes to extracting the most potential out of the car.

In the case of a wet track, the grip (G) variable changes significantly. It does these three things differently in the wet:

- The grip potential of the car goes down, making your overall friction circle smaller.

- The overall grip potential of the car goes down significantly in some areas of the track and hardly at all in others.

- The shape of the friction circle ovals, with the car losing more grip laterally than longitudinally.

The (R) and (D) do not change as a natural consequence of the rain, but we will change them slightly in response to (G) falling so low. This will ensure maximum performance out of the car by finding the ideal compromise of radius, grip and distance travelled.

The Game Has Changed

To the racing driver, these differences can make things pretty tricky when it comes to getting around a twisty piece of asphalt in the quickest possible time.

The performance driver hopefully already knows that the overall grip will obviously drop in the rain. But knowing the areas of the track where grip has plummeted versus areas where it’s only marginally reduced is key when it comes to staying safe and being fast out on track.

Knowing these areas is beneficial for both the racer and HPDE driver because it helps the racer go fast but also keeps the HPDE driver safe.

If the racing driver can find the ideal compromise of all 3 driver performance variables, he or she has done the best job possible when it comes to extracting the most out of the car.

In the rain, since (G) has been significantly reduced whereas (R) and (D) remain similar, the level of priority tends to sway more towards the (G) side of the equation even at the expense of (R) and (D).

Now we have a whole different ball game when it comes to line selection – and this is where it gets interesting.

It is now acceptable to significantly compromise (R) to find (G). Meaning, we now can go pretty far out of our way to find grip around the race track, even if it’s way off the normal dry line.

Why the rain changes everything.

Daytona 2015, SCCA Runoffs Spec Miata win

In the dry, (G) is fairly consistent across the width of the track. Therefore, we know that we can assign more and more priority towards expanding the (R) of the turn without compromising (G) very much if at all.

This is the fundamental reasoning behind why we expand the radius of the corner when finding “the line” and is the main principle behind basic line theory.

But in the wet, the (G) changes dramatically across the width of the track, so much so that it’s beneficial to sacrifice (R) to find (G).

So how do we identify where on the track these slippery spots may be? And what about the grippy spots? There are infinite variables at work here.

However, there are a few basics we know for sure that will serve as a generalized guide on how to approach driving on track in the wet.

If you forget everything in this article, remember this:

The dry line in the wet is usually a no go.

Here’s why.

When you look at a race track, you often see a “rubber line” around a corner. That is simply the path of rubber that you see on the track surface.

The rubbered up areas are where cars drive on the most. Wherever rubber is laid down on the track surface is where a tire was at one point sliding pretty hard. And if you add up all the cars that ever slid around that turn, you can imagine the build up!

In the rain, the oil from these rubbers comes to the surface and literally turns that section of road into an oil slick. We want to avoid this!

As such, it’s safe to assume we want to avoid the normal dry line.

The rubber line is a safe bet as to where the normal driving line is, and where the grip may not be in the wet.

(Slightly off topic, but one clarification… There is one major difference between the rubber line and the driving line. Think of the rubber line as the slightly earlier version of the driving line. This is because, especially at corner exit, when a car runs wide they tend to lean on the tire harder, laying down more rubber on what was slightly too early of a line in the first place.

Therefore, generally speaking we can assume that the normal driving line is a slightly later version of where the rubber line is. This serves as a good guide to finding the line in the dry, and consequently THE WET too!)

Wherever the dry line is – is where the wet line isn’t.

Now we have to start thinking about where the rubber is actually laid down on the track, and this goes beyond simply avoiding the dry line.

The rubber is not necessarily laid out a perfect, consistent fashion where dry line is.

The “rubber line” changes depending on how hard the tires are pushed into the asphalt under normal, dry conditions. And there’s some areas on the track that are on the normal line but DON’T have rubber laid down. That would be a win-win, as we would then benefit from (R) AND (G).

For example, a heavy brake zone area where a lot of passing occurs has the tendency of having a wider, more significant rubber line. This means that the slippery spots are not only more severe, but will be more than 1 car width wide, maybe even 2 or 3!

Another example may be the turn in to a high speed, sweeping corner. Typically, in faster corners under dry conditions, hand speed is slower and it takes a longer time to load the tire. This means that the rubber line may be present but in lower amounts approaching the turn in point to a fast sweeper.

Therefore, we can assume that grip may be more compromised across a wider portion of the track in a big brake zone corner. Vise versa in higher speed sweeping corners, where the rubber line tends to be narrower and not as drastic.

Think Like A Racer.

We have lost so much (G) that it’s beneficial to sacrifice some (R) and (D) in order to regain the performance variable that has diminished the most.

We are always making small adjustments to the priority of each variable to maintain the ideal balance of the three driver performance variables.

You know by now that typically in the wet we will purposely travel a tighter radius and a greater distance around a turn so that we will have higher grip in the corner. This will usually result in a net gain.

Finding The “Rain Line”

Because (G) is the driver performance variable that has diminished the most in the wet, we must pay extra attention to areas of the track that may have more grip, even if that spot is quite a bit off line from a radius perspective.

Going off line to find these grippy spots often results in a net gain even though the radius (and distance travelled) has been compromised.

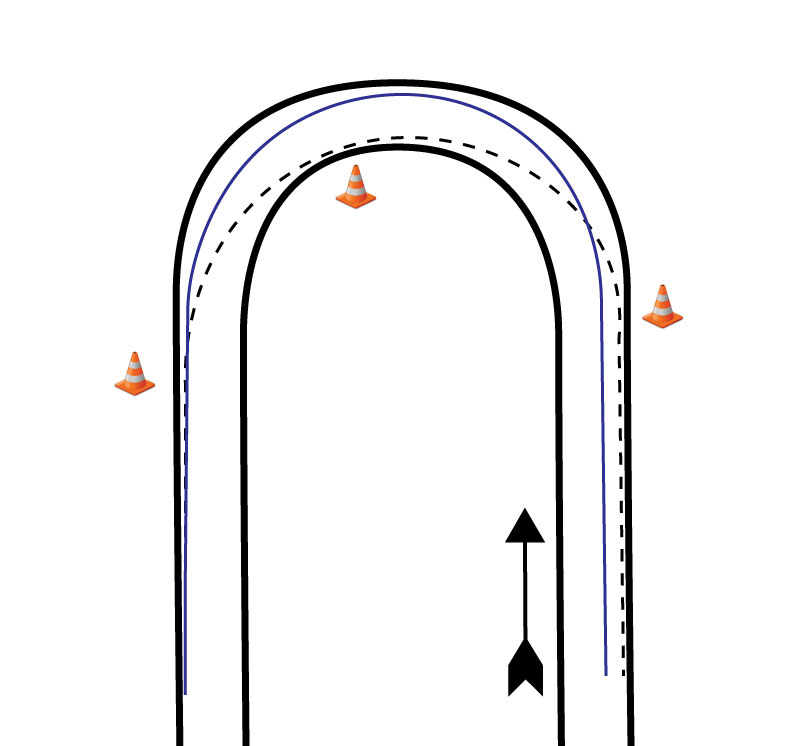

For now, let’s keep things simple. Take a look at the picture below.

Here you have your standard 180-degree hairpin corner. The black dotted line represents the traditional, geometric line biased towards a slight late apex. This is the typical line under dry conditions.

The rain line is illustrated by the blue, solid line. It’s important to note three things from this illustration.

- The rain line avoids the dry line as much as possible.

- When the rain line does inevitably cross the dry line near turn in, it does so at the most perpendicular angle possible.

- When the rain line inevitably crosses the dry line at corner exit, we want our hands as straight as possible.

We know that we want to spend as little time as possible on the dry line under wet conditions because that’s where the slippery spots are. Unfortunately, it is inevitable that we will eventually have to cross over that dry line at two points in the corner. So how do we deal with that?

Crossing On Entry

If we cross over the dry line at the most perpendicular angle possible, we will spend the least amount of time/distance crossing over it. This means we will have grip under our tires for a longer period of time/distance as oppose to transitioning across it at a nearly parallel angle. In that case, we’d end up spending a lot of time/distance on that slippery, dry line. No good.

This is why you see in the illustration I have “side stepped” the brake zone.

Crossing At Corner Exit

When we get to corner exit, we are left with two options.

- Keep the steering in pinching the exit, get to the grippy stuff inside of the track out point, straighten the hands and get to throttle.

- Open up our hands so that when we do get to the slippery spot we at least have less steering dialed in.

What to do here will mostly depend on the horsepower of the car.

If you’re in a lower horsepower car, the second option is usually better as you can’t spin the wheels as long coming out of the corner.

In a higher horsepower car, the first option is usually better. Since it’s going to take so long to get the power down due to wheelspin, you’re better off pinching off the exit a little more to get to the grippy stuff inside of the track out point.

Developing Your Rain Line From Basics – Pro

Now that you know the basics of rain line theory, I want to share with you some more advanced lines you can use in the wet. There are a couple other little tricks I use to not only gain grip (our primary goal in the wet) but ALSO radius at the same time. Download the free PDF guide below to learn my tricks and apply them in your own driving in the rain.

FREE PDF GUIDE

ADVANCED RAIN LINE THEORY

You’ll also receive updates and wisdom once per month. Unsubscribe at any time. We’ll never share your information.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed reading my article on high performance driving /racing in the rain! Perhaps now you have a little better understanding of my thoughts on the basic principles of rain driving. This content is the result of many years and decades of racing wisdom, but I work hard to define and clarify my viewpoints to help others be better track drivers.

If you have any questions about this article feel free to reach out!

Happy wheeling!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JONATHAN GORING

From 2006 Skip Barber National Champion to 2015 Spec Miata SCCA Runoffs Champion, and with the 2008 IMSA Lites title in between, I’ve been in the racing scene for quite some time. I’ve been fortunate to race against (and beat sometimes) the best drivers in the world currently racing in various top level motorsports.

I’m very passionate about the art/science of performance driving and want to share that passion with you.

WANT TO DRIVE FASTER THAN EVER?

Join my email list for monthly articles, driving tips, exclusive announcements on new things I’m working on and wisdom delivered straight to your inbox! You can unsubscribe at any time.